|

| Pilgrim

Street |

|

| The

Philharmonic Dining Rooms |

|

| St

Andrew's Church |

|

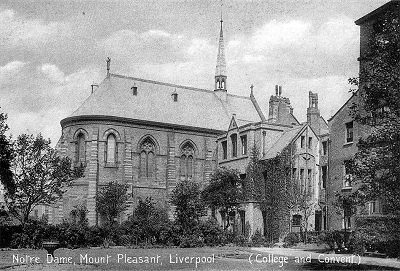

| Notre

Dame Chapel |

|

| Pilgrim Street,

a back street connecting Upper Duke Street to

Hardman Street, has converted coach houses at the

back of Rodney Street down one side that lend it

a definite old world charm. One of the old

buildings is now an interesting and atmospheric

pub, the Pilgrim, the entrance to which

is tucked away in a little alley down some steps.

|

| The Old School for the

Blind on

Hardman Street was a new building of 1849-51

replacing an original that had to be demolished

for the construction of Lime Street Station. It

has recently been nicely refurbished as a

restaurant and bar. |

| The

Philharmonic Dining Rooms, probably

Liverpool's most famous pub, was designed by

Walter Thomas (who also designed the similarly

grand Vines on Lime Street) for Robert

Cain's brewery and was completed in 1900. The

exterior (recently restored) is a kind of

Scottish castle fantasy with magnificent art

nouveau wrought iron gates. |

| Inside, there

is loving attention to detail with ornate

plasterwork, stained glass windows, glazed tiles

and mosiac floors, with which the Liverpool

University Schools of Art and Architecture were

extensively involved. Accomodation is on the

grand scale, the several large rooms lined with

dark mahogany panelling and decorated with

carving, the work of ships' carpenters who built

the lavish interiors of the ocean-going liners of

the time. The huge room at the back (the Grand

Lounge) was once the billiards room. |

| Perhaps the

pub's most celebrated feature is the gents'

toilet, a somewhat dog-eared

extravaganza

in mosaic and marble (ladies may arrangement with

the management). With an appropriate conflation

of allusions to music and alcohol, two of the

rooms are called Brahms and Liszt.

One of these has an imitation minstrel gallery,

while in the other is a fine stained glass window

dedicated to music. The inscription reads 'Music

is the universal language of mankind'. I'll drink

to that. |

| St Andrew's

Church, originally St. Andrew's Scotch Kirk of 1824, is located at the

northern end of Rodney Street and now, after

renovation, houses student accomodation. The

original churchyard remains, featuring a strange

pyramid of 1868, which is the tomb of railway

magnate William Mackenzie, said to be buried in a

seated position. |

| Notre Dame

Convent evolved and expanded from the

house at 96 Mount Pleasant beginning in 1851. It

became the Notre Dame Collegiate School

in 1902, a direct grant grammar school in 1946

and a girls' comprehensive school in 1983. It is

now part of Liverpool John Moores University. The

view from Mount Pleasant is rather flat and

haphazard and the rear is now cluttered with more

recent developments, but the c.1900 photo here

shows the impressive chapel as it once looked. |

| The northern end of Hope

Street is completely dominated by Liverpool

Metropolitan Cathedral, a magnificent counterpoise to

the Anglican Cathedral at the southern end. |

|

|

| The

Old School for the Blind |

|

| The

Philharmonic Dining Rooms |

|

| Notre

Dame Convent |

|

| The

Metropolitan Cathedral |

|