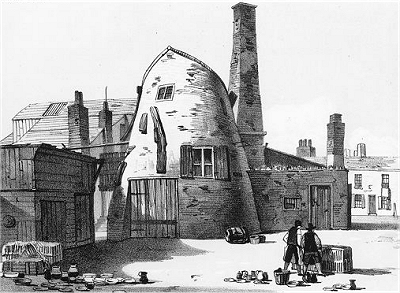

| William Brown-street

was within the last few years known as

'Shaw's-brow,' and is still so named by many who

have objected to the change, or who cannot forget

its old appellation. It was the main outlet from

Liverpool in the olden time by way of

Dale-street, and the 'Towns-end,' as that part of

Liverpool was called. It was a narrow steep

street. It derived its name and title of

'Shaw's-brow' from being the road to Mr. Alderman

Shaw's extensive potteries on the rising ground.

When Mr. Shaw was Mayor in 1794 he gave away the

whole of his allowance of £800 to the charities.

After Mr. Shaw had settled on the Brow, other

banks or potteries were opened, and increased in

number, until the vicinity became quite a

potters' colony. [...] The bottom of Shaw's-brow,

facing the Haymarket, was called St. John's

Village. Up the south side of Shaw's-brow were

the potters' dwellings. It is said that some of

these men, in the time of resurrectionism, were

in the habit of getting over the church-yard wall

and exhuming any newly interred bodies, taking

them into their houses, and selling them to the

medical students and others who purchased such

subjects. |

| On Shaw's-brow there

was once a well of famous water, which was

advertised for sale in the Weekly Advertiser of

the 17th November, 1758, at nine-pence per butt.

It is recommended by Mr. Parker, the proprietor,

as being 'so soft as to be excellent for washing

and boiling peas!' It may be recollected by many

as a never-failing well, supplying the engine of

an emery-mill. In the same yard was one of the

cones of one of the old pottery works. [...] The

widening of Shaw's-brow took place in 1852. The

houses were in some cases of rather a picturesque

appearance, some being constructed of wood, lath,

and plaster, and others of timber and brick. The

triangular piece of ground on which stands the by

no-means beautiful Wellington testimonial was

purchased by the Corporation in 1780. The

Townsend Mill stood at the western end. It was

taken down about that date. [SOL] |

|

|

| Pottery

on Shaws Brow c.1800 |

|